Introducing FACET – a framework for understanding real-world decision-making

This episode introduces a new framework for understanding and analysing decision-making. It is the first public airing of this framework - so quite a big deal!!

JAMIE WEST

Hello and welcome to the Unlocking Behaviour Change podcast, the show all about psychology and changing behaviour. My name is Jamie West and as always I am joined by Professor Robert West. Hello, good to be here. Hello Robert, and how has your week been?

ROBERT WEST

It has been very nice, a mixture of work and play and travel and music …

JAMIE WEST

And as for me, I've jettisoned my Fitbit. Yesterday, I got fed up with it. I didn't chuck it away, but I'm just not wearing it.

ROBERT WEST

As you know, I jettisoned mine some time ago because it had a really annoying feature that detected when you were walking and only showed information about that. And then when you wanted to see what the time was, you couldn’t find out!

JAMIE WEST

I think they do have options to change that!

ROBERT WEST

And I went through those options, and it changed briefly, and then it went straight back again …

JAMIE WEST

Fair enough. Other smartwatches to jettison are available, we should say.

Okay, so in this first season, we're talking about decision-making, and today is a big day because we're going to introduce a framework that we've been developing for some years. Mostly, I've chipped in a little bit here and there. We kind of trailed it in the very first episode, but today we are introducing the FACET framework of decision-making.

ROBERT WEST

Indeed, we are. It’s been a challenge coming up with a comprehensive framework - which is what we were seeking to do - a framework that could apply across the board to all the different kinds of real-world decisions that people are faced with - the challenge is that, of course, decision-making is such a varied process there's so many different things that go on or could go on and so many different ways in which people can make decisions that some people would even say it can't be done you know you can't create a unified framework.

JAMIE WEST

That was a challenge one of your friends pointed out, wasn't it ...

ROBERT WEST

And he knows more about decision-making than I do, at least in terms of the studies that have been done on it. However, I am not one to shy away from a challenge. And I like to think I actually started work on decision making, maybe even before he did, since it was going to be the subject of my PhD back in 1979.

I did a lot of work at that time and have been revisiting it ever since. However, the key is to have a unifying framework to understand decision-making, which I hope will become clear in this podcast and the ones that follow. Because if you don't, then whatever framework you use —there are other frameworks, which we'll mention briefly — will miss some really critical features of decision-making that you need to pay attention to.

For example, the most widely used one, certainly in economic theory and arguably in psychology, is called the subjective expected utility model.

JAMIE WEST

We talked about that, I think, in a previous episode.

ROBERT WEST

We did. We mentioned that it has several limitations, although it has been extended and developed into concepts like Prospect Theory, which contributed to Danny Kahneman receiving a Nobel Prize.

However, these models, which are intended to be quite general, aren't. And so, there are many important features of decision-making that they cannot and do not capture. We're attempting the near impossible: capturing those features while not discarding the insights these models provide, but rather incorporating them into a broader framework.

JAMIE WEST

And hopefully, that's what's coming my way. I frankly don't like prizes.

ROBERT WEST

I find them slightly embarrassing. So, I see a function for them, but I've never enjoyed receiving prizes, which is just as well because I haven't had many!

JAMIE WEST

I think we need to make a crucial distinction between – it's a bit boring, so let's get through this bit very quickly - but what's the difference between a model and a framework? Those two words again, a model and a framework.

ROBERT WEST

A framework is a set of linked constructs that help you to think about something in a systematic and structured way.

JAMIE WEST

That's what this is, isn't it?

ROBERT WEST

This is a framework, yes. It's not a model in the scientific sense because a model is a representation of something that specifies the relationships between various components of that thing in a way that allows you to understand it and make predictions from it.

And while I'm on the subject, a theory goes beyond that. A theory is a kind of model that specifically seeks to explain a set of phenomena. A model can be purely descriptive, allowing you to represent something that enables you to make predictions. So a model of stock market shifts, for example, could be a statistical model or a time series model that you would then use to predict what's going on. It's not explaining what's going on, but it's telling you what it looks like so that you can then go on and make a prediction.

A theory goes behind the superficial data to say, well, these are the causal processes going on. And the framework, which is what we're talking about here, is a set of ideas and constructs and ways in which those are related, which helps you to think in a structured way from which you can build one or more models or theories.

JAMIE WEST

So I once tried to read Stephen Hawking's A Brief History of Time. And a few pages in, my brain became frazzled, and that feeling is returning to me now as we go through these things. But you know what? I think I understand it well enough. This framework, the FACET framework, will help us understand and sort out decision-making so we can examine it in a more helpful way.

ROBERT WEST

Yes. Without necessarily making specific predictions in specific areas. However, it can be used to build models in particular areas and domains, such as financial decision-making, consumer choice, piloting an aircraft, and dating decisions, among others. It can provide a framework from which you can construct a kind of working model to make specific predictions in those domains. And then we get the Nobel Prize.

JAMIE WEST

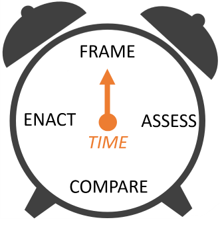

Yeah. Okay. So, we're going to get into this FACET framework. What does it stand for? F-A-C-E-T.

F stands for frame. A stands for assess. C stands for compare. E, enact. And T is time. That's a lot to take in all at once. Maybe we start with F for frame.

ROBERT WEST

Frame refers to the processes that we undertake at the beginning of the decision-making journey, in which we construct the decision question. What is the question I'm trying to answer?

Much of the time, we simply go about our lives, responding to the world around us or attending to tasks. But every now and then, something happens which causes us to pause and think.

And those things can be threats, they could be opportunities, they can be tasks that we have to do, or they can be goals that we have in our head, okay?

So, threats, opportunities, tasks, or goals. When faced with one of these, and we don't have an immediate response that we can implement - that triggers the decision-making process. And the first thing we do is construct a decision frame.

And the decision frame - we're going to cover these in more detail in another podcast - but the decision frame includes the question that you ask yourself. What shall I do? Shall I do this? How much of this should I invest, for example? So it's the kind of what, which, how much type of question. That's the decision frame. And that then dictates what happens next, because that means that you're starting to formulate what your options are and how you're going to go about analysing them.

JAMIE WEST

And these frames, they can be quite - I want to say - subtle in that you might say, “Shall we go to an Italian restaurant or an Indian restaurant, for example?” Or you might say, 'Where shall we go for dinner?' One of those is a binary choice, which has already limited it quite a lot. And where shall we go? Oh, we could go anywhere. And that's a big difference, a binary decision versus an open-ended decision.

ROBERT WEST

That's right. And that is the key dimension, I think, on which we should really concentrate our attention: how closed or open the frame is. So when, let's say, you're presented with an advert on Instagram, which is for, say, a new bit of audio processing software. The way it's presented to you makes you think, 'Shall I buy this or not?' It's a very closed decision. Where, in fact, often a better decision would be a more open one: “OK, that's an interesting idea.” I didn't even know you could have audio software that did that. Let me look and see what the options are. It might not be the one that's in front of me. And you might go even further and say, “Well, actually, do I even want to be in this space at all?” And you can extend the whole decision-making process to something much, much broader.

The way we frame the decision is often conditioned by what's presented to us: whether it's an opportunity, a threat, or something else. And one of the ways in which decisions go wrong, as we'll discuss in more detail later, is when you frame your decision in a way that is too limited, too restrictive: “Shall I or shan't I?” rather than the “Which of these shall I choose?” or “What shall I choose?”

JAMIE WEST

It's a big topic that I think we'll keep coming back to, because it's one of the first areas where a decision can go wrong. One of the advantages of the FACET framework is that it allows you to examine each of the different areas – framing, assessing, comparing, enacting, and timing. And you can go: where have things gone wrong?

Let's move on to the A, which is assess. So that's what? Assessing the options?

ROBERT WEST

Yes, it's assessing the options and the relevant information associated with those options. And in that, one of the things that has become apparent in the research that's been done on decision making is that there are two kinds of modes in which people make those kinds of assessments.

One is a sort of pros-and-cons type mode. You evaluate the costs and benefits, the good and bad aspects, the negatives and positives of the different options you're considering. And then we'll see later, you make a decision. You come to a view on which of those you want to pursue.

That's one way of doing it. But in an awful lot of decision-making, that's not how we do it! What we do is try to match the options to a sort of pattern that we already have in our heads or on a piece of paper, in a checklist, or whatever it might be.

So instead of saying what are the pros and cons of this, we say what are the features of this decision problem that I'm faced with? And given those features, what seems to be the appropriate response? For example, when you're piloting a plane and a warning light comes on, you have checklists that you either have in memory or must retrieve or display on the screen, which tell you what to do if certain conditions are met.

You've got what amounts to a set of if-then rules. And this is sometimes referred to as pattern matching or mapping. There are many different names given to it, but it's more of a procedural, if-then type process rather than an evaluation process, a sort of pros and cons type process.

JAMIE WEST

And we have ways of saving ourselves from doing too much work ...

ROBERT WEST

I think what you may be referring to here are heuristics that we use. These are kinds of rules of thumb or shortcuts. And these can be things that are just very general that, you know, humans do that we know in trying to sort of reduce the cognitive load. But others are things that are very useful. They can be very detailed, created by experts in a field, and they provide us with a sort of map—a pathway on how to do things.

Let’s take just an example. You’re trying to choose a candidate for a job, and you've got 100 applicants. There's no way you can fully evaluate all of them. So, what are you going to do?

You go through a multi-stage process. You'll have an initial screen, in which you might apply a very abbreviated version of the pros and cons type analysis, in which you'll say, well, candidate A, well, they're good at this. They're not very good at that. They're excellent at this, and so on. And you create a sort of profile for them.

Now, you only do that for a very small number of criteria. This is a model known as the elimination by aspects model. But you do it for a small number of criteria because you can't possibly do it for all of the things that you're interested in, in the depth that you need. That means you can then rule out a lot of options.

Obviously, the danger with that, as we know only too well, is that because you haven't gone through the full process, you may well throw out the best person. It's a risk, but it's just pragmatics.

Then, you might go through your shorter list in more detail now. And eventually, you might invite candidates for an interview, a second interview, and so on. So, you have this multi-stage elimination by aspects type of process going on. That's a kind of heuristic to deal with cases, for example, where you have a large number of options that you need to whittle down so that you can ultimately make a choice.

JAMIE WEST

So, in the FACET framework, the next element is ‘compare’. And it sounds like assessing and comparing are sort of often done in tandem.

ROBERT WEST

It's essential to understand in the FACET framework that it's not a linear process. You don't go frame, assess, compare, enact - we'll deal with ‘time’ in a minute - but it's not that you do one and then the other.

I suppose you could in a sort of idealised situation. But very often in real-world decision making, you're jumping backwards and forwards or you're doing things at pretty much the same time. In the model I mentioned earlier, the elimination by aspects model, you're doing a bit of assessing, a bit of comparing, and a bit of reframing —assess, compare, reframe, and so on. And then you move through the process until you arrive at a final decision frame, which is, “I've got these two candidates, which shall I choose?” Or if there aren't any suitable candidates, “Shall I re-advertise?” or whatever …

JAMIE WEST

So, as you're making a decision, you’re often changing the frame, actually. You might start off with, “Who shall we hire for the job?” And then at the end, you might be, “Shall we hire Amanda or Katie?”

ROBERT WEST

And that's one of the many crucial things about treating decision-making as a real-world issue, rather than the sort of idealized type of decision tasks that you often see in the scientific literature … that you can reframe, you can reassess .... Decisions don't have to take place over minutes; decisions can take place over years and they can be redone and re-evaluated as we talked about last time.

When it comes to ‘compare’, this is the process where you're saying “I've got this information about this option, and I've got this information about this option. How do I put them together?” And this is where the key concept we need to convey is the decision rule. What is the rule that I'm going to apply in order to make this choice?

Commonly occurring rules that you see in the literature are ones like maximax, minimax, satisficing and so on. I'll briefly tell you about those, as they should resonate with people once we provide real-world examples.

The maximax rule is the idea that you choose the option with the maximum positive outcome. So you're trying to maximise your gain. Now that might come, and usually does come, at a potential risk of losing everything. This is your risk-taking for the sake of achieving the maximum possible outcome type of option. And of course, we know people who will tend to make decisions in that kind of way. Or who, in certain circumstances, will make that kind of decision.

Then you've the maximin, which is the opposite of that. It involves taking all the options, which is the one that I can be confident will give me the least bad outcome. That's the safe option, the insurance option.

There is a well-known and studied rule that I think somewhat relates to this. And that's what's known as satisficing. That rule recognises that the decision-making process takes place over time. It takes resources. And you can't always get the best option, regardless of the decision rule you choose. And so what people very often do is they say, I'm going to adopt the good enough rule. I'll review the options. And as soon as I find one that'll do, that's fine. I'll choose that. I think that pretty much captures my own decision-making when I'm out shopping for clothes. If I see something that looks good, then I'm off.

JAMIE WEST

And that, for other recovering perfectionists out there, will be familiar because good enough tends to be better than perfect, which you sort of never reach, and so you never make a decision because perfect is unattainable. So you're often being taught to just try and go for good enough. That's okay.

Okay, so we're just sort of skating over the surface here. The penultimate element in the FACET framework is ‘enact’. Tell me about that.

ROBERT WEST

Decisions don't stop at the point where you've made your comparison. A decision doesn't mean anything unless it ultimately leads to some kind of action. And so the ‘enact’ part of FACET is all those things that we do, actions that we take, thoughts that we have, feelings that we have, that go into turning that choice, that sort of theoretical choice that's in your head, into action.

And then, very importantly, for many decisions that we make, we evaluate how it's going. Evaluating the results of that and potentially going back into the decision process again and saying, well, actually, I'm not sure that was the right thing to do or that needs to be tweaked in some way.

And again, this is an important feature of real-world decision-making, as opposed to the hypothetical decisions that are often studied, where this process doesn't end even with the action taken.

You have the evaluation as well. And of course, in big decisions that involve spending large sums of money, whether it's developing a drug or developing a new product or deciding on a new configuration for your armed services or whatever it might be - these are things that you will be evaluating.

And there's a science around how you go about that in order to feed back into changes that you might make to the decision process as you're going along. So, enact is the part that turns the whole thing into concrete actions, and then evaluates how those are going, so that you can ensure you get what it is you're looking for.

JAMIE WEST

And one example we give in the book that we're writing on this, 'Reflect: The Science of Real-World Decision Making', just a plug for when it comes out, is medical dramas, like one of my favourites, the TV show ‘House’ starring Hugh Laurie.

And they often come up with a provisional diagnosis then they treat. And of course, whatever they think the illness is, it is usually not. And they have to go through that process multiple times before, and at the end of the episode, they finally uncover the truth. But each time they learn something. And actually, each time, according to storytelling structure, they make things slightly worse!

ROBERT WEST

They actually almost always make things massively worse!

JAMIE WEST

That's how a story's got to work.

ROBERT WEST

It's got to escalate. In House, they actually use the enact part of the decision as part of the assess part! So what they do is they - in my opinion, ludicrously and unethically - skate through, assess, compare, go straight to enact so that they can see what going on.

However, it does capture something very important: that often, you have to take action. You have to take action to figure out what's going on and gather the necessary information to make an informed decision about the right course of action. So that action might turn out to be the right thing to do, and in which case, great. However, if it isn't, it has provided you with information that you can then use to adjust. That only works, obviously, in the real world. If you've got the time and resources to do that, to collect the information, evaluate it objectively, and the consequences of you getting it wrong aren't going to be catastrophic.

JAMIE WEST

And now, we're nearing the end of the episode, so we need to address the last element, which is ‘time’. So we've had frame, assess, compare, enact, and now time. And it is absolutely appropriate that we should end ‘on time’, as it were. Time will one day end us all, just as it began us!

ROBERT WEST

Time is not a process that people go through, but rather a feature that must be considered at every stage of the process. It is not an optional extra: considering time in the decision-making process.

Decisions take place over time. They're always - even if they're not framed in this way - they're always under some kind of time pressure. Not least because sometimes, even if there isn't an external deadline, you've got to get on with other things. You can't just spend your whole life just making this decision. So even when it doesn't seem like it, there's always some kind of time pressure.

Time pressure conditions every aspect of the decision-making process, from framing to assessing, comparing, and enacting, among others. So, if we go back to the elimination by aspects model, for example, and other types of heuristics, the reason we need them is that we don't have time to conduct a comprehensive analysis of all the necessary information to make a thorough evaluation of the options.

But time pressure, whether it's externally generated or internally generated, has a number of consequences in the way we make decisions that have been studied and which we need to be aware: which includes two, for example, that I'll just briefly mention and we can discuss at greater length in another podcast.

One is when you can't clearly find a good option in the time that you've got. So there's time pressure. And you can't see a good outcome. What people often do then is the sort of headless-chicken type thing. They flip from one option to another, to another, to another, and then time runs out. And whatever they were on at the time when the flag falls or the clock ticks over or the alarm goes off, that's what they end up having to do. And that's obviously not an effective decision-making strategy, but it's a very commonly used one that's often employed under time pressure when there's no satisfactory option.

The other way in which people can respond to time pressures when, for example, there may be a satisfactory option and others which are not, is to just simply curtail the search, curtail the process and say, 'Right, that's it. I've got to this point.' And then, after having made the decision, cognitive dissonance kicks in, and they defend that decision to the hilt. And they will … instead of at a later point when there may be options to do something about it and modify it or go down another route, no, we've made the decision. We're going with it. That's it.

JAMIE WEST

And just a reminder to listeners, cognitive dissonance is when you hold two conflicting beliefs in your head, and it makes you feel uncomfortable.

ROBERT WEST

And so you try and deal with it. One way to deal with it is to boost one of the beliefs and discount the other. You say, no, that's it. This is the right decision. Don't talk to me about this decision. These are just a couple of examples of how time pressure can significantly influence the way a decision is made.

JAMIE WEST

I'm looking forward to coming back to these because each of these elements is so full of nuance and complexity, and is so useful to learn about because once you see the differences and the subtleties in all of these choices that we're making, it means you can be more conscious and make better decisions, and be clearer when something goes wrong, what went wrong, so you can fix it for next time.

Okay, well, that was a really fascinating introduction to the FACET framework, which I'm super excited about. My first rung on the ladder towards a Nobel Prize, and I'm looking forward to collecting that. I don't know how long it takes between coming up with a theory and getting the Nobel Prize. How long?

ROBERT WEST

It can take a long time. It can take until you're nearly dead. I mean, it's better to get it while you're alive.

JAMIE WEST

Yeah, a posthumous Nobel is no good, is it really? Anyway, that's all for this week. Remember to subscribe to the podcast, and you can purchase our books, Energise and React, via the links in the description. And we will see you next time on Unlocking Behaviour Change.